Introduction

Remember History classes in primary and secondary school? Because I sure can’t. Brunei’s history has always circulated around Sultans and the strange wars they went through in order to reclaim their position as a monarch. Cock fights? Are you kidding me? Our history, if I may be frank, was like a badly written Saturday Night Live sketch.

History has always been against women, which is why there is currently a global resurgence in fighting for women’s rights. Whether Brunei today is fighting for further benefits for women is not something I can confirm, although we have seen great progress in women’s education in the past thirty years, and we have two women in the Legislative Council who are continuously bringing up women’s issues. I started the website “Why Brunei Needs Feminism” and the submissions it’s received has been overwhelming. The question I pose to myself as a Brunei feminist is this:

How would I know if there has been progress in gender equality?

Because, again, being frank, I can’t. Believe it or not, there is little recorded history of women in Brunei during British rule.

Main(back to Top)

Was this the case in Brunei? I don’t have a confirmation saying whether it did or did not happen. In short, I don’t know, and this is the reason:

It is with a heavy heart I tell you this story about when I met several people from The Brunei History Centre (PSB). I asked them what the role of women were during British rule. I asked because I was trying to figure out if it would be a good topic for my Masters (it totally is.) I wanted to know if women had politically motivated, sexually centred relationships with British men, which happened in Malaysia. I am keen to know in order to motivate myself to further my education and to have something tying me back to the country. I asked the question so I’d have resources to make the study concrete. I would write the proudest thing I have written in my life with this topic.

And a PSB man said, “Well… I can’t answer that because there has been no study.” That was his answer. Not even an exaggeration other than translating it to English.

A woman from PSB later approached me and laid the ball on me. Her conclusion was similar:

There is no study on women in Brunei in our history under the Brunei History Centre. At all.

That was the first conclusion, and I wasn’t too upset about that. However, her second conclusion was, “Women had no education and didn’t work. They were not allowed to go out of the house.” Basically, the patriarchy was strong with this one. As was the over-exaggeration.

Remember—unless you studied overseas—when history teachers kept talking about Padians (river traders)? Those ladies selling perishable goods on boats from houses to houses while donning seraung (traditional weaved hats)? That is evidence of women’s role. Padians was something I held on to strongly when I was in university writing about women’s role in Brunei. Hence, I asked the PSB lady, “How about Padians? They had an economic role, right?” And she emphasised the point:

Women did nothing. Women had no role. Women, your great-grandmother, your great-great grandmother, female nenek moyangs were nothing but sex machines that were meant to produce boys, and girls to further oppress. Only after 1984 were women free.

I swear—my late grandmother—who was the epitome of women’s emancipation during British rule—was rolling in her grave trying to get out and punch this lady on the boob. This breaks my heart. Can you imagine if the world had given up on Roman history? Can you vision historians looking at Egyptian Hieroglyphics and conclude them as ‘Cool Squiggly Things’? Or closer to home, what if we ignored the fact that the father of Mathematics were Muslims?

PSB’s conclusion is not so much “no study” or that “women had no role”. It signifies that women’s history is unimportant and not crucial to nationalism. Sure, continue studying the lineage of the monarchy, but there are other areas of Brunei that should also be studied because they are important too. We are ignoring so much of our history as it is. Ask me why I’m not a super nationalist like a lot of people, it’s because I can’t identify with the monarchy because I’m not a part of the elite. I’ve never gone to war because of cock fights, let alone fight over a man with another woman. I identify myself most as a woman. There is no history of me and the progression of my gender in my country to be really proud of or fight for.

I’ve always wanted to have further insight on Brunei women’s role during the time when the British came. Whether there is a deep anthropological thesis on the subject, I don’t really know. There’s just no accessible database for it. If you have come across something in line to what I’m searching for, please don’t hesitate to leave a message below. It would be useful in understanding our history, how far has our progress been and how much we have or have not changed. At the very most I can manage is this piece. You might find it sloppy or inaccurate—a part of me feels like it’s sloppy and might not be accurate—because it’s hard to do research like this when a body specifically set for research in history is not doing anything nor are helpful. But I sincerely hope this will motivate others to delve into this topic either as a part of their career or educational research or in my case, for fun.

WE CAN DO IT.

Economic(back to Top)

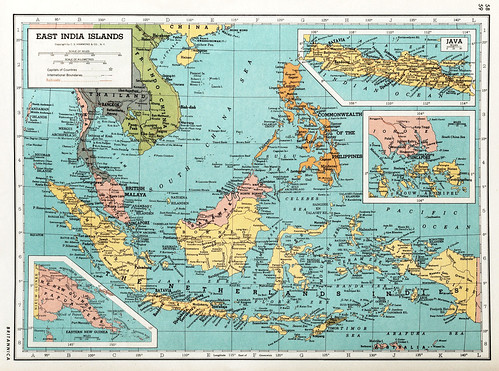

Participation of women in the workforce helps build a prosperous economy, as well as, higher Gross Domestic Product (GDP), even as a cleaner. During the World War eras, women were a massive source of employment when men went to the field. Historically, women played an important role in the economy of Southeast Asia where they were mostly responsible for the money in a family. This is in part because if men were the ones holding the money, they would misuse it for gambling and SHOPPING SPREES!!! Through the anthropological lens of gender behaviour in Southeast Asia, there is a conformity in men’s spending conduct, this paints the possibility that the same could have happened in Brunei during the British era of rule. Go to the markets in Thailand and Indonesia now and you will see the people selling perishable goods are women. This is a tradition has lingered for over a century (or more).

There is evidence that exists until today showcasing that women in Brunei played an important economic role. The most prominent role is that of Padians, existing even before the British entered Brunei.

The image of Padian has been used famously in history books of Brunei where women would travel on sampans (flat wooden boats) wearing teraungs selling perishable goods to villagers. Although Padians are rare today—they venture more in remote areas of Kampong Ayer sans teraung—there is evidence showing that their role as a trade facilitator has not depleted. With trade locations such as Tambing relocated on land areas have made it easier for Kampong Ayer residents to access—not to mention safer as the threat of water taxis are imminent—it is possible that Padians have merely shifted from boats and large hats, to dry land and roofed canopies.

Walk around the Tambing area and you will find that a majority of the sellers are elderly women. Although physical environment has changed, there is also a maintenance of the status quo from British rule. During British rule, poverty and the lower class divide were more visible. In order to uplift the financial burden of a family, women had taken business roles by trading services for money. Such services include tailoring and the selling of foodstuff to government offices. Outside of these small ventures, women were also working in various enterprises. 57.3 percent of women involved in the working sector in 1960 were active in agriculture, forestry and fisheries, which fell down 6.2 percent in the early 1980s before Independence from the British. This fall, however, led to a rise of women’s involvement in social services such as professional work, something that has continued until today. From here, social change can be attributed to females being allowed to go to school and have a career, and seen as necessary in order for Brunei thrive economically and socially after its independence.

Cultural(back to Top)

By and large, women played a significant role in upholding the cultural traditions in Brunei, something that is easy to observe but also easy to ignore in our society as we look past the norm. In fact, if it was not for women, the cultural tradition of jong sarat (traditional woven fabric) as a form of wedding clothing would not exist today.

Originating from Kampong Sungai Kedayan and spreading to its nearby areas like Kampong Bukit Salat and Kampong Lurong Sikuna, tenunan (woven fabric) is an art that has prevailed until today. Tenunan is a form of art and tradition of garment weaving. Currently it is popularised as an article of clothing used for the bride and groom during weddings.

These cultural traditions ties back to women’s economic role. They are also a way to get money which helped with the finances of a family. Although it seems insignificant, in the current era where the government is urging us to look into our traditions, we have often ignored that women has played a large part in preserving the identity of our nation, opting instead for the argument where women had no role as if my grandmother just sat down on a chair like a zombie all her life until she was forced to die.

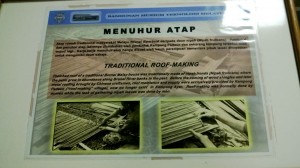

The best, I think, I’ve found from my research is this gem above from the Malay Technology Museum, Kota Batu. This is the epitome of what I think society should achieve: a cooperation between genders in order to form something, where credit is given to both male and female in order to formulate something strong and necessary like a roof. To ignore a role as easy as roof making is insulting to women, especially when women are the ones making these roofs.

The metaphor to this is beautiful when reflected in the research I have done for Open Brunei. Women were the ones making roofs while men were the ones gathering materials. It’s a wonderful shift from the traditional perception that men do the hunting while women doing the gathering. Women played such an integral role in roof making, in providing food in everyone’s bellies and giving them shelter from the tropical weather.

But the best thing about the simple job of roof making is this: It wasn’t a job for one gender, it was cooperation between females and males, where their strength lies in the hand of each participant to create one thing that is required and crucial at the centre of society. The job wasn’t dominated by a gender, it was cooperation in order to build a house: the central body in which the primary socialisation of gender perspectives come from.

The world is a massive and vast space, and if we continue to ignore the importance of women in society other than baby-making machines—women are, after all, half of the population—that society will crumble. In the current era where the government focus is Wawasan (Brunei’s Vision) 2035, it is disheartening to think that the possibility of my and other women’s role in society now will be forgotten. And someone—someone like me—would have to go back to square one in seventy years’ time to go to the extent I’m currently going in order to find information about women’s roles. And our current roles are awesome: mothers, graduates, scientists, Olympians, writers, artists, IT developers, Minister, etc.

We are currently not only breaking glass ceilings, but we’re also forming flower decorated escalators in order to help the future generation of women to climb up, look at the shattered glass ceiling and continue on to break social stigmas against women. But if the future generation do not have any research to tell them the extent we’ve currently gone through in order to break that glass ceiling, then what is the use of making women’s relevancy in society important now, and begs the question:

Why should we even bother playing a role when we are seen as historically insignificant.

Research Approaches (back to Top)

I would like to thank all the cafes that tolerated me as I ran my hand through my hair repeatedly, slammed the table, talked to myself, and made their space as my home for six hours at a time sometimes. I would also like to think all the baristas who asked me if I’m okay because I realise how awkward it might have been to witness someone looking like they’re having a breakdown*. I would like to apologise for the narrow approach this article had taken. I am mostly sorry for not having more racial intersections as my sources were limited, but I am absolutely interested to know more on how other Puaks and Chinese women experiences were during the British rule. * At no point of writing this article did I have a breakdown.

I would like to thank all the cafes that tolerated me as I ran my hand through my hair repeatedly, slammed the table, talked to myself, and made their space as my home for six hours at a time sometimes. I would also like to think all the baristas who asked me if I’m okay because I realise how awkward it might have been to witness someone looking like they’re having a breakdown*. I would like to apologise for the narrow approach this article had taken. I am mostly sorry for not having more racial intersections as my sources were limited, but I am absolutely interested to know more on how other Puaks and Chinese women experiences were during the British rule. * At no point of writing this article did I have a breakdown. Share your thoughts(back to Top)

- Have you done research on Brunei women during British rule? Did you come across the same issues as Teah?

- In what ways can we chart experiences of women in contemporary society? How about experiences in previous decades?

- Do you agree with Teah’s point, “Why should we even bother playing a role when we are seen as historically insignificant”?

Share your experiences below!

good jobs..eyes opener

Very insightful..

This might be a roundabout way of researching on women’s roles, but would the female members of the royal family be a place to start? It may be a route focusing solely on the elite, but perhaps there will be some further information to be found by researching the sultans’ wives and mothers. Frequently in royal families, a male monarch’s women (especially the mother) could exercise influence as coequals.

Please keep in mind I am sadly ignorant of Brunei’s history in general, so I apologize if the question comes off as uninformed.

Hi Teah, I enjoyed yr views and just wanted to share a similar experience when I was writing an essay about Bruneian women writers while in UBD in 2015. It was very frustrating as research on gender in Brunei is limited and even less where literature is concerned. In the end, I’d to rely on student dissertations, newspaper articles, and feedback from colleagues. For me, the question was – why are there so few women writers in Brunei? Brunei Malay literature at least has Norsiah Abdul Gapar, but she does not have a counterpart in the world of Anglophone writing. I have since published an article titled, “Bruneian women’s writing as an emergent minor literature in English,” which can be found in World Englishes if you’re interested. I hope to see more of your writings in future.

Hi grace!

Thanks so much for this comment. I agree that there are definitely a lot of gaps in terms of our research on women in Brunei. While there are many people studying on it for academic reasons, too many have gone unnoticed or publicised, and worse so that our history and exhibitions (of whatever kind) tend to focus from a men’s lens when documenting Brunei institutions.

As for women’s writers in Brunei–I’ve always been bothered by the constant throwing of Norsiah’s name and no other women, whether it is in English or Bahasa Melayu. I think there are plenty of women writers in Brunei, and several have had their work published in English under Dewan Bahasa. I think the problem has always been failure to empower women and providing them the chance to further succeed in literature. I’m seeing a lot of women approaching writing themselves now. I had to do a writer’s lunch a few months ago and 98 percent of the people who came were women because I think it showed women’s understanding that showing up is necessary for women in order to advance their career.

I also currently run a website for Brunei writers, with 100 percent women writing staff if you’re interested in checking us out!: http://songketalliance.com

PS: I have saved your paper and will be reading it!